Home > Blogs > The Right Fit: Choosing Patient Interfaces for Effective Non-Invasive Ventilation

The Right Fit: Choosing Patient Interfaces for Effective Non-Invasive Ventilation

- Published on:

The Right Fit: Choosing Patient Interfaces for Effective Non-Invasive Ventilation

- Published on:

On this page

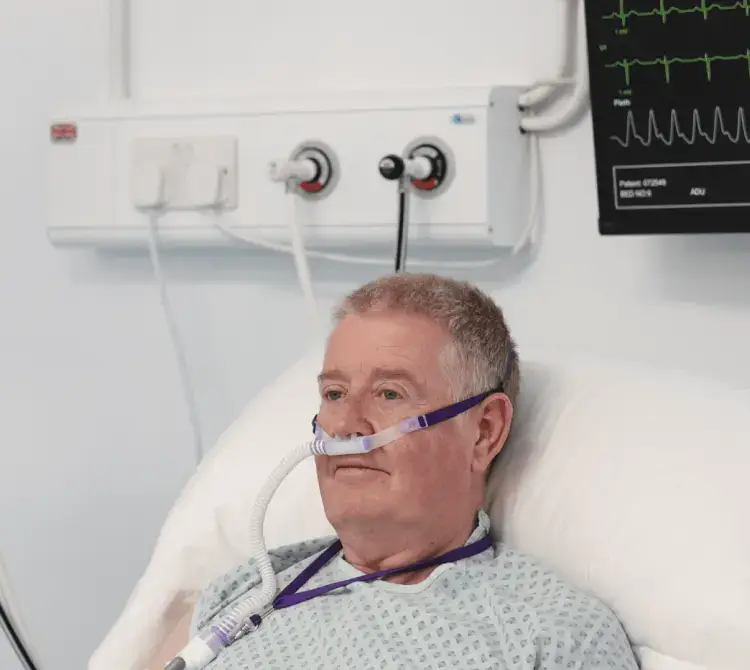

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) are widely used therapies and effective treatments for individuals with respiratory failure, sleep apnoea or cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. The ventilator, flow driver, interface, and mode/setting selections are all critical components of effective non-invasive therapy delivery.

In the adult acute care environment, several NIV interfaces are available, including nasal masks, oronasal masks, mouthpieces, total face masks, and helmets. Early studies found that intolerance of therapy due to the mask interface could lead to treatment failure.1 The common issues related to NIV interfaces include skin pressure sores (particularly on the bridge of the nose), claustrophobia, and general mask discomfort.2

When selecting the best interface, the clinician must consider various factors, such as patient tolerance, facial skin breakdown, medication delivery, and device availability. The primary clinical goal of using NIV is to minimise the need for intubation, invasive mechanical ventilation, and the associated adverse effects.3

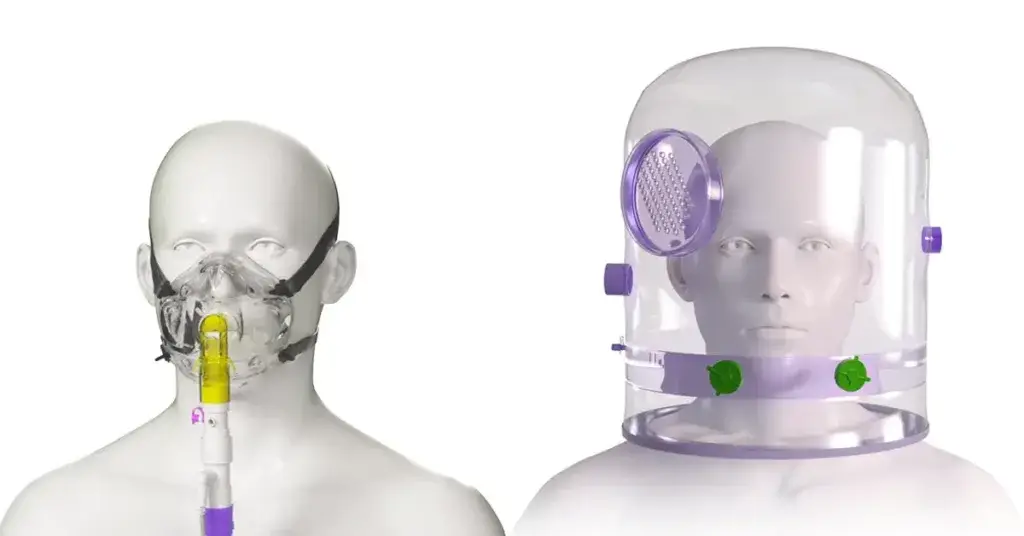

Two common interfaces are oronasal masks and helmets, each with its own set of advantages and considerations. In this blog, we will explore the differences between delivering NIV via an oronasal mask versus a helmet in the acute adult setting.

Oronasal masks

In clinical settings across Europe, face masks stand out as the predominant interface for non-invasive therapies.4 There is considerable data to support the clinical effectiveness of oronasal and total face masks.5,6

Traditionally, face masks, both oronasal and full face, are used most often. The choice between mask types is based on patient comfort, face contour, and equipment availability. Face mask NIV has been shown to effectively improve oxygenation and reduce inspiratory demand. It covers both the nose and mouth, creating a seal to ensure that pressurised air is delivered effectively.7 Oronasal masks are available in many sizes and models and require accurate measurement to adapt to the anatomy of the patient’s face.

The British Thoracic Society recommend that a full-face mask be used, especially for those patients who are mouth breathers, that a range of masks and sizes are available, and staff involved in delivering NIV need training in and experience in using them.8 Having a range of masks available is also useful when skin breakdown occurs. Facial pressure ulcers from CPAP masks appear among 10% to 33% of CPAP users with nasal bridge ulceration being the most common problem (5–10%)9 .

Alternatively a total face mask extends its coverage to include the mouth, nose, and eyes and may be used to mitigate skin breakdown or reduce the risk of skin damage. While they may offer enhanced comfort during extended treatments, their superiority over oronasal masks has not been definitively proven.5 Given that they are generally better tolerated, total face masks could serve as an alternative in cases where mask intolerance is the primary cause of NIV failure.

However, oronasal masks come with certain drawbacks, including a lack of protection from vomiting, potential nasal skin injuries, nasal congestion, dryness of the mouth, eye irritation, difficulties in speaking, and the risk of inducing claustrophobia.1

Key points to consider:

Comfort and Familiarity: Oronasal masks are familiar to many clinicians and are often the first choice for CPAP or NIV therapy. They come in various styles and sizes, allowing users to find a comfortable fit.

Focused Delivery: Directs pressurized air precisely to the nose and mouth.

Effective for Mouth Breathers: Individuals who breathe through their mouths can benefit from oronasal masks as they cover both the nose and mouth, preventing air leaks.

Potential for Discomfort: Some users may experience discomfort, irritation, or pressure sores around the nose and mouth due to the mask’s contact with the skin.

Risk of Air Leaks: Achieving a proper seal with an oronasal mask can be challenging, and air leaks may occur if the mask has not been adequately measured to fit the patient’s face.

Helmet NIV

The use of helmet-based NIV experienced a resurgence amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily driven by safety concerns for healthcare professionals. It was proposed that helmets with an inflatable neck cushion pose the lowest risk of aerosol droplet dispersion. Both the helmet and face mask contribute to a reduction in the work of breathing, effectively mitigating the spread of aerosol droplets and minimising room air contamination.7

Furthermore, helmet CPAP has shown efficacy in improving hypoxemia and lowering the incidence of intubation in cases of acute hypoxic respiratory failure. When equipped with antiviral filters, the helmet interface proves to be a more dependable and secure option for healthcare workers, enhancing safety during the provision of care.10

In June 2022, a review by NHS England and the National Infection Prevention and Control proposed removing NIV from the current UK Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGP) list, as seven studies consistently indicate that NIV is not linked to elevated aerosol generation, and concentrations are lower than those from regular breathing.11

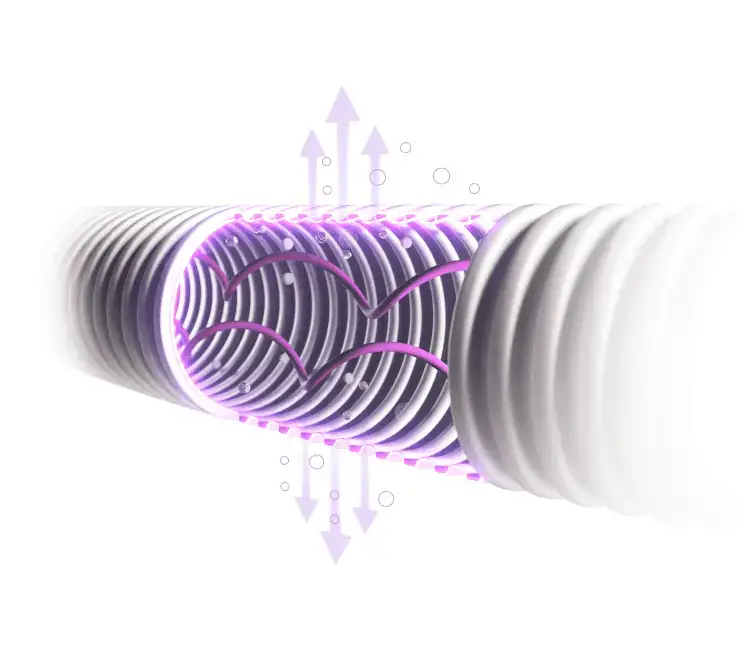

The helmet is a transparent hood with a soft collar that contacts the body at the neck and/or shoulders but does not contact the patient’s face. The size of the interface is determined by the patient’s neck circumference. The helmet has a volume of around 18L and behaves as a semi-closed mixing chamber with its own “helmet ventilation”. As such, part of the patient’s exhaled gas is not eliminated from the helmet and mixes with gas coming from the inspiratory limb of the circuit.12

The helmet interface does not apply pressure to the face, but the neck and under the arms (where straps are used to stabilise the helmet) and these areas need to be monitored for any skin integrity issues. While there may be differences in practice regarding humidification during NIV, humidification improves comfort and may have a positive impact on tolerance of therapy.

Key points to consider:

- Reduced Facial Contact: Unlike oronasal masks, helmets minimise direct contact with the face, reducing the risk of skin irritation and pressure sores.

- Freedom of Movement: Helmets provide greater freedom of movement, allowing users to change sleeping positions without compromising the seal.

- Reduced Claustrophobia: Helmets offer a more open and less confining experience compared to masks.

- Access for Care: Allows healthcare providers access to the patient’s head without removing the helmet.

- Effective Seal: Helmets often provide a more secure seal, reducing the likelihood of air leaks compared to oronasal masks.

- Higher PEEP levels can be used with minimal leak or eye irritation: It is uncommon to reach PEEP levels higher than 5–8 cmH2O during face mask NIV while levels of 12–15 cmH2O are easily achievable with a helmet.6

- Less Conducive to Mouth Breathing: While oronasal masks cater to both nose and mouth breathers, helmets may be less suitable for individuals who predominantly breathe through their mouths.

However, the helmet approach might not be suitable for all cases. Issues like noise from the CPAP device, potential air dispersion, and the bulkiness of the helmet can pose challenges for some patients. Additionally, ensuring an airtight seal around the neck area might be more challenging compared to the precision fit of an oronasal mask.

Choosing the Right Method

The decision between an oronasal mask and a helmet for delivering NIV or CPAP depends on various factors. Patient comfort, medical requirements, ease of use, and the patient’s ability to tolerate the device play pivotal roles in determining the most suitable approach.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of Non-invasive therapies lies in their consistent use. Whether it’s through an oronasal mask or a helmet, healthcare providers aim to optimise oxygenation and breathing support, tailoring the approach to meet the specific needs and comfort of each patient.

While both methods, oronasal mask and helmet CPAP, offer distinct advantages and considerations, the choice between them should prioritise patient comfort and compliance, ensuring the uninterrupted delivery of non-invasive therapies for improved respiratory outcomes.

References

- Piraino, T. (2021). Noninvasive Respiratory Support. Respiratory Care, 66(7), pp.1128–1135. doi:https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.09247. Noninvasive Respiratory Support – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Bachour, A., Avellan-Hietanen, H., Palotie, T. and Virkkula, P. (2019). Practical Aspects of Interface Application in CPAP Treatment. Canadian Respiratory Journal, [online] 2019, pp.1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7215258. Practical Aspects of Interface Application in CPAP Treatment – PMC (nih.gov)

- Antro, C. et al . (2005). Non-invasive ventilation as a first-line treatment for acute respiratory failure: ‘real life’ experience in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal, 22(11), pp.772–777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2004.018309. Non-invasive ventilation as a first-line treatment for acute respiratory failure: “real life” experience in the emergency department – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Crimi, C. et al (2010). A European survey of noninvasive ventilation practices. European Respiratory Journal, 36(2), pp.362–369. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00123509. A European survey of noninvasive ventilation practices | European Respiratory Society (ersjournals.com)

- Hess, D.R. (2013). Noninvasive Ventilation for Acute Respiratory Failure. Respiratory Care, 58(6), pp.950–972. doi:https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02319.Noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Chacur, F.H. et al (2011). The Total Face Mask Is More Comfortable than the Oronasal Mask in Noninvasive Ventilation but Is Not Associated with Improved Outcome. Respiration, 82(5), pp.426–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000324441. The total face mask is more comfortable than the oronasal mask in noninvasive ventilation but is not associated with improved outcome – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Rosà, T. et al (2022). Non-invasive ventilation for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, including COVID-19. Journal of Intensive Medicine, [online] 3(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jointm.2022.08.006. Non-invasive ventilation for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, including COVID-19 – ScienceDirect

- Davidson, A.C. et al (2016). BTS/ICS guideline for the ventilatory management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure in adults. Thorax, [online] 71(Suppl 2), pp.ii1–ii35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208209.BTS/ICS guideline for the ventilatory management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure in adults (bmj.com)

- Gefen, A. et al (2020). Device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. Journal of Wound Care, [online] 29(Sup2a), pp.S1–S52. doi:https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2020.29.sup2a.s1.Device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention | Journal of Wound Care (magonlinelibrary.com)

- Deniz Çelik (2023). NIV: Noninvasive Ventilation via Different Face Masks/Helmets. Springer eBooks, 2, pp.119–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29673-4_14. NIV: Noninvasive Ventilation via Different Face Masks/Helmets | SpringerLink

- NHS England. Classification: Official Publication Approval Reference: C1632 a Rapid Review of Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGPs). 9 June 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/C1632_rapid-review-of-aerosol-generating-procedures.pdf

- Chiumello, Davide, et al. “Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation Delivered by Helmet vs. Standard Face Mask.” Intensive Care Medicine, vol. 29, no. 10, 1 Oct. 2003, pp. 1671–1679, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12802491/, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-1825-9

Abby Lennon

Clinical Nurse Adviser, RN

Abby works alongside the Clinical Education Team to provide support and education to healthcare professionals using her knowledge and experience as a registered nurse working in respiratory wards and intensive care units over the last eight years.