Health Literacy: A guide to improving patient communication

- Published on:

Health Literacy: A guide to improving patient communication

- Published on:

On this page

What is Health Literacy?

‘People having the skills, knowledge, understanding and confidence to access, understand, evaluate, use, and navigate health and social information and services’ (Public Health England).

Why is it important?

According to Health Education England (2020), Healthcare organisations need to ensure that the information they provide, and the way it is communicated, are at an appropriate level for most of the population to understand. Low health literacy is one of the main barriers preventing healthcare professionals from transmitting information to people in their care effectively (Chapman et al 2020). According to the National Literacy Trust (2017), one in six adults in England has very poor literacy skills. Health literacy is also linked with patient activation, which is a measure of a person’s knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their own health and well-being and is a crucial enabler of self-care (NHS England 2018).

What is the issue?

The average reading age in the UK adult population is 9 years old (Rowlands et al 2015). This applies to 43% of the population. Half our patients will be affected by this issue. This same number is seen all over world in other first world countries such as America, Europe and Australia. Written information in healthcare is written at a 14–16year-old reading level, so we have a large gap between what we provide and what is understood by our patients. The three main things that could help are developing skills in the public through improved education, enhancing healthcare professionals’ communication skills, and improving written health information.

We also know that three out of four patients don’t know the side effects of their medications and one in four patients don’t know why they are in hospital in the first place (Nicholson Thomas et al 2017). People will struggle with managing health conditions linked to that admission going forward.

People with low health literacy may find it challenging to manage long-term conditions, take their medication properly, follow healthcare professionals’ recommendations, and understand the lifestyle changes required for preventing ill-health (Lamb and Berry 2014). People with low health literacy may also find it challenging to manage the health of their children and/or anyone else they care for. In community and primary care settings, low health literacy may mean that people do not seek medical attention in a timely manner (Protheroe et al 2009). The lack of routine healthcare visits and the lack of steps taken to prevent ill-health mean that people are likely to present at more advanced stages of disease, with a higher risk of negative health outcomes including death. Patients who struggle to understand their health information are at increased risk of missing follow up appointments. Being unable to read the information about the plans post-discharge or being unable to navigate the hospital leads to missed appointments, which are a poor use of staff time and resources.

People with low health literacy are more likely than others to be admitted to hospital for urgent health issues (O’Conor et al 2020), while people who are discharged from hospital without understanding their diagnosis and/or new medicines are more likely to be readmitted (Cloonan et al 2013, Bailey et al 2015).

Techniques to improve how we communicate

1. Teach Back.

Tell people information using simple language and avoid jargon. It is our responsibility to make medicine understandable to the public, they aren’t expected to know what we are talking about. Ask them to explain back to you what you’ve told them, so you know they’ve understood you. If it hasn’t quite landed, try again with different words, try pictures or similes.

2. Chunk and Check.

If you are giving lots of different information, break it down into sections. Teach the patient each section and get them to repeat it back to you. Then summarise the sections at the end so you know everything has been understood.

3. Keep it Simple.

Think about how you would explain things to an 8-year-old child and start there. Keep your sentences short. Stick to the same terms for things. If you say high blood pressure for example, don’t then say hypertension, people won’t realise they are the same thing under different names.

4. Offer Help.

Assume that nobody can read. If you start on that assumption and adjust your style once you know the person you won’t miss people. People who can’t read won’t tell you that. There is shame and stigma around it.

Tools to improve written work

If you are creating any content for patients or the public, check the readability by using an online readability checker. The Flesch Reading Ease Score is a tool available online, you should aim for a score of above 80 to make it understandable for the general public.

How Flesch Reading Ease Scores Translate to Reading Difficulty

Reading Ease Score | Descriptive Categories | Estimated Reading Grade |

|---|---|---|

90-100 | Very Easy | 5th Grade |

80-90 | Easy | 6th Grade |

70-80 | Fairly Easy | 7th Grade |

60-70 | Standard / Plain English | 8th and 9th Grade |

50-60 | Fairly Difficult | 10th to 12th Grade |

30-50 | Difficult | In College |

0-30 | Very Difficult | College Graduate |

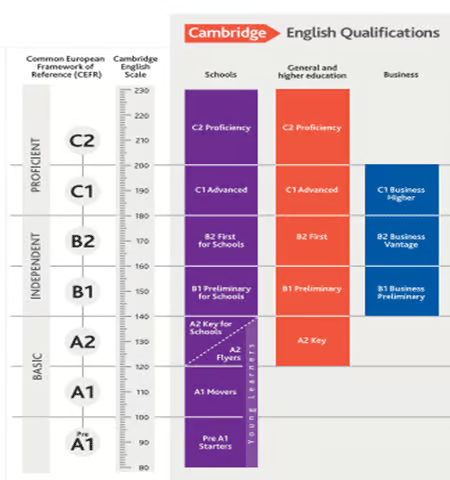

Challenge your own ideas about the words you use in your day-to-day life that aren’t medical jargon specifically. There is a scoring system called the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). This grades words on a scale from A1 to C2, you should aim for words that are A1 and A2 level.

References

Byrne D (2022) Understanding and mitigating low health literacy. Nursing Standard

Chapman E, Haby MM, Toma TS et al (2020) Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: an overview of systematic reviews. Implementation Science. 15, 1, 14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0974-3

Cloonan P, Wood J, Riley JB (2013) Reducing 30-day readmissions: health literacy strategies. Journal of Nursing Administration. 43, 7-8, 382-387. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31829d6082

Eichler K, Wieser S, Brügger U (2009) The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. International Journal of Public Health. 54, 5, 313-324. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0058-2

Health Education England (2020) Health Literacy ‘How to’ Guide. library.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/Health-literacy-how-to-guide.pdf (Last accessed: 7 July 2022.)

Lamb P, Berry J (2014) Heath Literacy – The Agenda We Cannot Afford to Ignore. Community Health and Learning Foundation, Leicestershire.

National Literacy Trust (2017) Adult Literacy. literacytrust.org.uk/parents-and-families/adult-literacy (Last accessed: 7 July 2022.)

NHS England (2018) Module 1: PAM: Implementation – Quick Guide. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/patient-activation-measure-quick-guide.pdf (Last accessed: 7 July 2022.)

Public Health England, UCL Institute of Health Equity (2015) Local Action on Health Inequalities: Improving Health Literacy to Reduce Health Inequalities. assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachmentdata/file/460709/4a_Health_ Literacy-Full.pdf (Last accessed: 7 July 2022.)

Rowlands G, Protheroe J, Winkley J et al (2015) A mismatch between population health literacy and the complexity of health information: an observational study. British Journal of General Practice. 65, 635, e379-e386. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685285

O’Conor R, Moore A, Wolf MS (2020) Health literacy and its impact on health and healthcare outcomes. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 269, 3-21. doi: 10.3233/SHTI200019

Dominique Byrne

Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Portsmouth Hospital University Trust